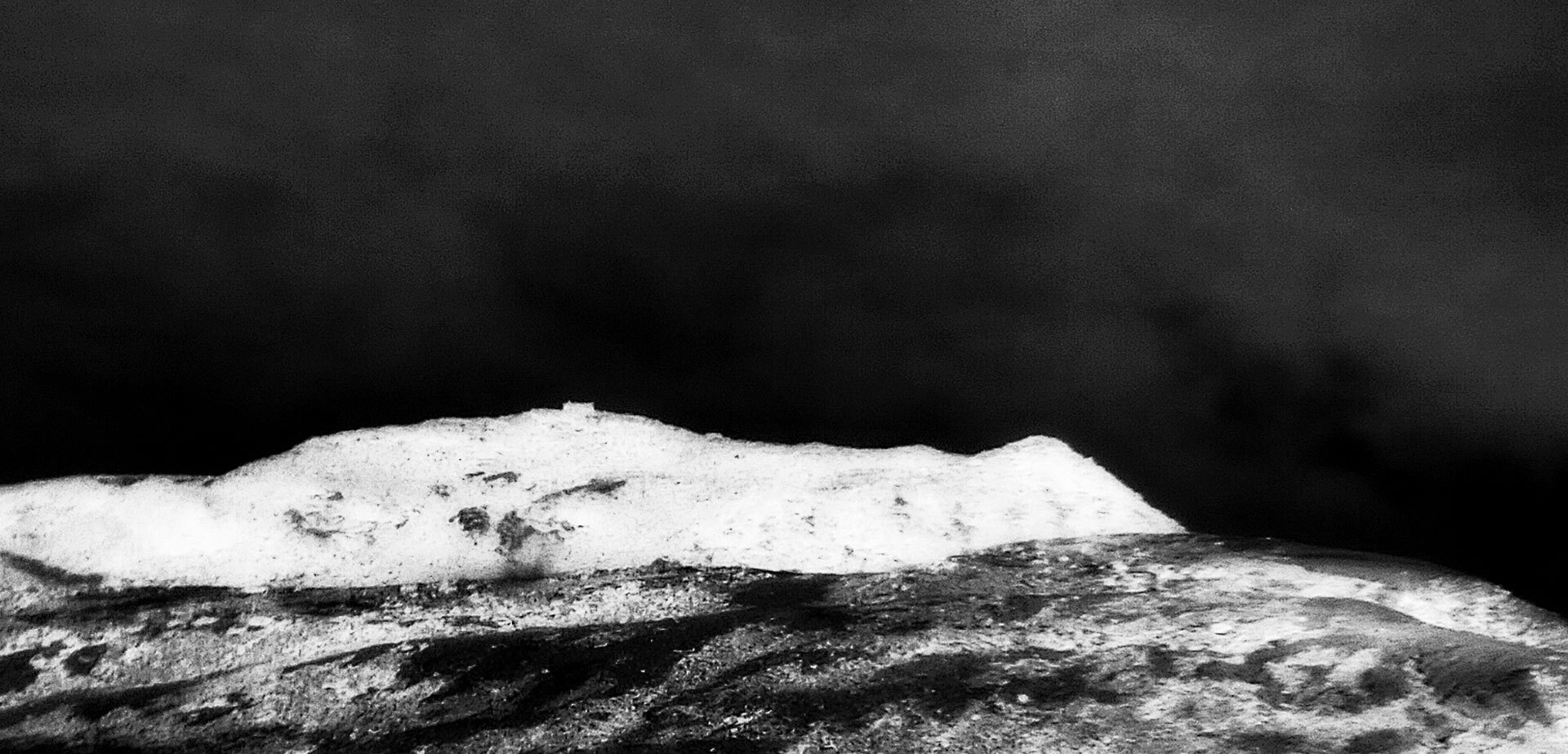

With Stasis Peak, ASTASU—the ambient moniker of composer Ryan Eastham - reaches a new creative threshold. The album emerges from years marked by personal loss, long periods of introspection, and a deliberate shift away from rhythmic certainty toward more fragile, atmospheric spaces. Speaking with striking candour, Eastham reflects on rediscovering the instinctive joy that first drew him to sound, the tension between structure and emotion, and how grief reshaped both his process and his artistic priorities.

ASTASU

ASTASU